OKRs: Objectives and Key Results – the best goal-setting technique

OKR is an abbreviation for Objectives and Key Results. It’s a very popular goal-setting technique, primarily used by top management and teams to help execute strategy.

The main purpose of OKRs is to set crystal clear yet ambitious goals, create alignment, and regularly measure progress while promoting commitment. The magic behind OKRs is in its simplicity and result-based orientation.

If you are in a leadership position or if you are a goal-oriented individual, you’ve almost certainly heard of OKRs.

Whether you would like to know more about the best way to implement OKRs, or you’re still skeptical of the technique, in this concise guide we’ll lead you step by step towards OKR mastery and at the same time answer all the important questions you might have about the technique.

We’ll do that without any prolixity or over-complication, as discussions around OKRs might sometimes be.

- Understanding the OKR basics: Objectives and Key Results

- 1. What different types of OKRs do we know?

- 2. What is the ideal time frame for OKRs?

- 3. How many OKRs should there be?

- 4. How often should you monitor Key Results?

- 5. What is the best way to measure progress on KRs?

- 6. Is there a difference between KRs and KPIs?

- 7. What is the best process for setting OKRs?

- The six main benefits of OKRs

- 1. Focus

- 2. Alignment

- 3. Commitment

- 4. Tracking

- 5. Stretching

- 6. Agility

- Frequent mistakes when setting OKRs

- 1. Not being sure how to write down OKRs correctly

- 2. Not measuring KRs (set and forget)

- 3. Maintaining “business as usual”

- 4. Setting too many OKRs

- 5. Using OKRs for things they aren’t intended for

- Practical examples of OKRs

- The OKR tools and additional resources available

- A brief history of OKRs

Understanding the OKR basics: Objectives and Key Results

An OKR is nothing but a goal written in the following form: “We will [objective], as measured by [key results].”

As the name suggests, an OKR consists of two parts – an objective (O) and a few connected key results (KR) – usually 3 to 5. An example of a OKR would be the following (set as a quarterly OKR):

|

Objective |

Key results |

|

Start generating leads with inbound marketing or We will flood our sales team with inbound leads (if the company culture is more informal) |

|

Now let’s look closely at each of the two OKR parts:

An objective

An objective (O) is a statement of what is to be achieved. It’s the thing you want to accomplish - the final outcome. The questions behind an objective should be “Where do we want to go?” and “What do we want to achieve?”

An objective should be set in an ambitious, concrete and significant way. The idea of this question is to identify a few core goals for the organization that can lead to the most progress, while giving everything else a lower priority.

In OKRs, an objective should be so ambitious that it feels a little uncomfortable, in order to push you out of the comfort zone, but on the other hand, an objective should also be short and easy to memorize.

How formally the objective is written can be adjusted to the company culture. The most common mistake is the objective being written as a key result. A correctly set objective is an antidote to confusion or poor execution.

Key Results

Key Results (KRs) are how progress is measured. The question behind KRs is “How will we know we got there?”

KRs must be measurable and verifiable. They need a starting and target value. If a KR doesn’t have a number, it’s not a KR.

When all key results are completed, the objective is achieved. Key Results should be based on anything that can be measured, such as:

- revenue,

- performance,

- engagement,

- growth etc.

There shouldn’t be more than five key results per objective; ideally three to five.

There must also be clear evidence of completion for each key result. Examples of evidence are metrics, change logs, notes, reports, etc. The evidence must be credible and available to all OKR parties.

Leaders should stand firmly behind a few OKRs that bring clarity, a compass, and baseline for assessment to team members.

The general recommendation is that a KR should be written as an outcome, not an output:

- Output – a task, to-do, requirement (for example: sales plan)

- Outcome – value, impact, behavior, change, ROI etc. (for example: 10 new customers)

Initiatives

Since we need activities and outputs to achieve an OKR, there’s often a third category in the OKR methodology, called initiatives.

Initiatives are all the projects, plans, tasks and activities that help to achieve the objectives. The main question behind Initiatives is “What are we going to do to achieve the goal?”

For the above OKR (generating leads) initiatives would be:

- Write 12 long-form blog posts to target relevant keywords

- SEO optimize every blog post based on the SEO checklist

- Distribute each blog post on social media

- Create and test 10 forms to optimize the conversion rate

Now that you understand the main philosophy behind OKRs, let’s go through some of the most frequently asked questions:

1. What different types of OKRs do we know?

We know of five main different types of OKRs. There might be more, but let’s not overcomplicate things.

The first distinction is how ambitious the goals are and how many unknowns there are regarding their execution. Based on those variables, we can identify committed OKRs and aspirational OKRs.

- Committed OKRs – These are the commitments of the team, with a precise plan (initiatives), resources, timeline etc. There’s a solid plan on how OKRs will be achieved.

- Aspirational OKRs – They are “moonshots” that are very risky. It’s also hard to predict their outcomes. These goals require much more experimenting, without a solid plan.

The second differentiation is based on a timeframe or cadence. We know three different types of OKRs based on the timeline difference:

- Strategic Cadence: A high-level goal, usually set annually for a time span of one year or even longer. A company OKR should unite the company toward a few long-term goals.

- Tactical Cadence: A shorter term OKR for teams, usually set quarterly.

- Operational Cadence: Achieved with the weekly check-ins (more about that later), usually meant to monitor progress on KRs.

2. What is the ideal time frame for OKRs?

We’ve partly answered the question in the previous paragraph, but let’s be even more explicit at this point.

The company (strategic) OKRs should be set on an annual basis with a time span of 1 – 3 years, whereas teams (tactical) OKRs should be set on quarterly basis with a quarterly time span.

|

OKR level |

Planning frequency |

Time span |

|

Company |

Annually |

1 – 3 years |

|

Teams |

Quarterly |

100 days |

|

Execution monitoring |

|

Weekly basis |

These are general recommendations, but you can be flexible. The time frames can be adjusted according to how fast a company or specific team is moving towards their goals.

3. How many OKRs should there be?

It’s really important not to have too many OKRs. The upper limit is seven, and the fewer the better.

You can even take a step further by having one single company OKR to really unite and bring a company forward, an idea presented by Christina Wodtke in her book Radical Focus.

Imagine focusing your key people on one single goal - the most important one. It gives you a feeling that you can move mountains. Remember, strategy is deciding on what not to focus, and radical focus can lead to breakthroughs.

Have too many goals and you will struggle with decision paralysis on which direction to move. If everything is important, nothing is really important.

4. How often should you monitor Key Results?

The KRs should be measured on a weekly basis. A goal without ruthlessly consistent implementation is merely a wish; a nice dream.

That’s the hardest and the most important part of having OKRs – being consistent in monitoring the progress; something that can be done during weekly OKR check-ins.

The Weekly Check-ins are periodical events in which the team tracks accomplishments. They review the objectives, key results, and initiatives and check the progress on the latter. It makes sense to track the OKR weekly check-ins with a time tracker.

In addition, teams can discuss how confident they are about realizing an OKR and reflect on how they can improve. To promote agility, teams can also talk on the weekly check-ins if any adjustments to OKRs are needed.

5. What is the best way to measure progress on KRs?

There are two recommended ways to measure progress on KRs – a simple one, and something a little bit more complicated. The simple version is binary and the more complicated style is a decimal scale.

Since Google introduced the decimal scale, frankly, it’s become the most popular way.

- Binary – Achieved (yes) or not achieved (no)

- Decimal scale – You use a scale from 0.0 to 1.0 and grade progress at the end of each cycle (on such a scale 0.0 – 0.3 means a failure, 0.4 – 0.6 means some progress, and 0.7 – 1.0 means delivery)

One additional recommendation is to make KRs public. Full transparency, if implemented correctly, should lead to better commitment and a more fair business environment.

6. Is there a difference between KRs and KPIs?

KPIs - key performance indicators – measure the overall performance or health of a business initiative. They measure business as usual and don’t tell you what needs to be changed or improved.

KPIs can be associated with “a dashboard” showing how a business is preforming.

KRs can be associated with a “roadmap.” They define and measure advancements, and are much more than just performance measurement, but rather a framework for setting and achieving goals.

KRs should guide you towards the destination. However, sometimes a KR can actually be a KPI. A company should use and combine both, since KRs and KPIs complement each other.

7. What is the best process for setting OKRs?

The best way to set OKRs is through a series of OKR workshops. For top management who sets OKRs on the company level these are most often off-site strategic planning workshops that can take a few days.

The goal is to make sure a company goes in the right direction. For teams this usually involves shorter tactical planning meetings.

If you are implementing OKRs for the first time, it’s highly recommended to start only with top management or one really well-functioning team. First you should run it as an experiment with one cross-functional team, and only then scale it across other teams.

In the OKR workshops OKRs can be set in two ways:

- Top-down: Leaders set objectives and key results

- Bottom-up: Team members set objectives and key results

When scaling OKRs across the whole company, it’s important to consider the following:

- As a general recommendation, OKRs shouldn’t be set department by department but on a cross-functional team level that will bring a company forward.

- The team OKRs should be closely connected to company OKRs.

- There should be a healthy mix of top-down and bottom-up OKRs.

It’s also highly recommended to get an OKR coach or consultant to help educate employees and coordinate the process.

In the same way as SCRUM always requires us to have a SCRUM master in a team to make sure the process is being correctly followed, so must there be someone responsible for implementing OKRs correctly.

Now that we have covered the frequently asked questions regarding OKRs, let additionally overview other relevant and useful topics regarding the technique.

The six main benefits of OKRs

There are five main benefits (plus one extra) of setting OKRs, presented with the abbreviation F.A.C.T.S. These benefits, as described by John Doerr, the venture capitalist who popularized the technique, are:

1. Focus

Confusion and vagueness are the two biggest enemies of achieving goals. With OKRs, crystal clear goals are set, along with a roadmap and measurement protocol.

That also means priorities are set and everyone has a clear picture of what to focus on.

2. Alignment

In teams and organizations, alignment among team members or all the organizational layers is crucial. It’s hard to achieve a goal if everyone is pulling in their own direction.

Having clear objectives and regularly measuring progress creates alignment that leads to achieving the desired goals much faster. It’s also important that OKRs are public and visible to everyone in the organization.

3. Commitment

When setting OKRs, it’s important to get a commitment from the key parties involved. Based on the alignment, everyone should commit to working hard towards the end goal.

The clear sign of commitment is if resources and schedules are relocated in favor of the new objectives. In addition, using an OKR app or visualizing OKR in the office are important signs of commitment on the organizational level.

4. Tracking

Key Results are all about measuring the progress towards goals. It’s a crucial element of the technique. Only what we measure can we manage. Weekly checking is recommended after setting the OKRs.

With checkups, it’s also beneficial to do a short reflection, namely analyzing why and how the team is progressing towards the objectives and how they can improve.

5. Stretching

The OKR methodology encourages the setting of ambitious goals that are outside of the comfort zone. These goals encourage us to achieve much more than just “business as usual”.

The mantra of the OKRs is having a simple idea that drives 10X growth, so stretching is definitely an important benefit. One sigh that you are not stretching the objectives enough is if everything is always competed and achieved.

6. Agility

An additional benefit of OKRs (especially quarterly ones), together with regular weekly check-ins is that it promotes agility, meaning with shorter goal-setting cycles organizations can quickly respond to change.

In this sense it’s important that OKRs are reviewed and updated regularly.

Teams should be retrospective about these events, asking themselves if there are any adjustments needed to the OKRs. Some companies combine SCRUM methodology with OKRs to achieve an even greater sense of agility.

Frequent mistakes when setting OKRs

No goal setting technique comes without its drawbacks, and we can make some crucial errors if the implementation is not done correctly. A few common mistakes when setting OKRs are:

1. Not being sure how to write down OKRs correctly

The technique really is simple, but since it’s so straight to the point, it’s sometimes difficult to write down the OKRs.

There might be unnecessary pressure if OKRs are written correctly (to be written as outcomes, making sure KRs are measurable, etc.). You might also struggle with choosing the right KRs.

The advice to help you overcome this challenge is quite simple: Practice makes perfect. After writing down several OKRs, it gets easier and easier to set the them in the best way possible.

2. Not measuring KRs (set and forget)

The second most common, and to be honest even more frequent, issue is not regularly monitoring and measuring KRs. You might be proud of yourself when setting OKRs, but then completely forget about them.

Regularly monitoring and measuring the progress is mandatory. It’s about being transparent and radically candid about how fast you are moving towards your objectives.

A useful recommendation when setting OKRs is also to determine a directly responsible individual (DRI) for a specific OKR. This person should then also be responsible for the weekly check-ins.

3. Maintaining “business as usual”

OKRs are about stretching the team, going beyond “business as usual” and 10xing your success. That means objectives must be set in an ambitions and inspirational way.

Not being ambitious enough is also one of the common mistakes teams make when setting OKRs.

If the majority of OKRs are achieved, that’s an obvious sign the goals are not ambitious enough. In Google, reaching 70 % of the OKRs is considered a success.

4. Setting too many OKRs

If you have too many goals, usually you achieve none of them. In most cases it’s much better to go 10 steps in one direction (first you must be sure it’s the right direction) than taking 1 step in 10 different directions.

Too many directions leads to confusion, procrastination, and not knowing where and how to start. Seven OKRs is the maximum amount that’s still manageable.

But many agree having 1 – 3 OKRs is even better, since it promotes better focus. And as mentioned, to be even more united and focused as a company, you can choose only one OKR.

5. Using OKRs for things they aren’t intended for

OKRs are not KPIs, to-do lists or employee evaluations; OKRs are a tool to help execute a company’s strategy.

They are different from other goal-setting techniques, especially in terms of encouraging very ambitious goals, having a simple execution roadmap and making sure you regularly measure the progress.

The important part of OKRs is to push companies and teams outside the comfort zone and encourage them to go for the big bets. They also encourage teams to correctly prioritize goals - to go after the biggest opportunities.

At this point it’s also worth mentioning that OKRs should be separate from compensation, otherwise people will strive to play it safe and not go for ambitious enough goals.

Practical examples of OKRs

Now that we’ve covered all the theory, let’s look at a few practical examples of OKRs:

|

Objective |

Key Results |

|

Make our customers supper happy |

|

|

Create outstanding customer support |

|

|

Successfully launch a new product |

|

|

Make our brand known in the industry |

|

|

Reach profitability with healthy cash-flow |

|

|

Become the fastest moving company in the industry (while going in the right direction and making sure quality doesn’t suffer) |

|

|

Win the Super Bowl |

(Source for the last OKR: Measure What Matters) |

Going through the examples there are a few additional important things to mention:

- The best OKRs are set for the company level or cross-functionally with the goal being to focus, align, and motivate the whole company on all levels and across all departments.

- Nevertheless, many times OKRs are set on a department level, meaning they are accounting OKRs, online marketing OKRs, design OKRs, engineering OKRs, etc. There’s nothing wrong with setting OKRs on the department level, although it’s highly recommended to also have company level OKRs,

- And as it goes for company level OKR’s, it’s usually much harder to involve support departments (admin, accounting, etc.) than teams directly involved with a product or marketing/sales. So, sometimes for the company level OKRs, it’s okay if you can’t involve every single department.

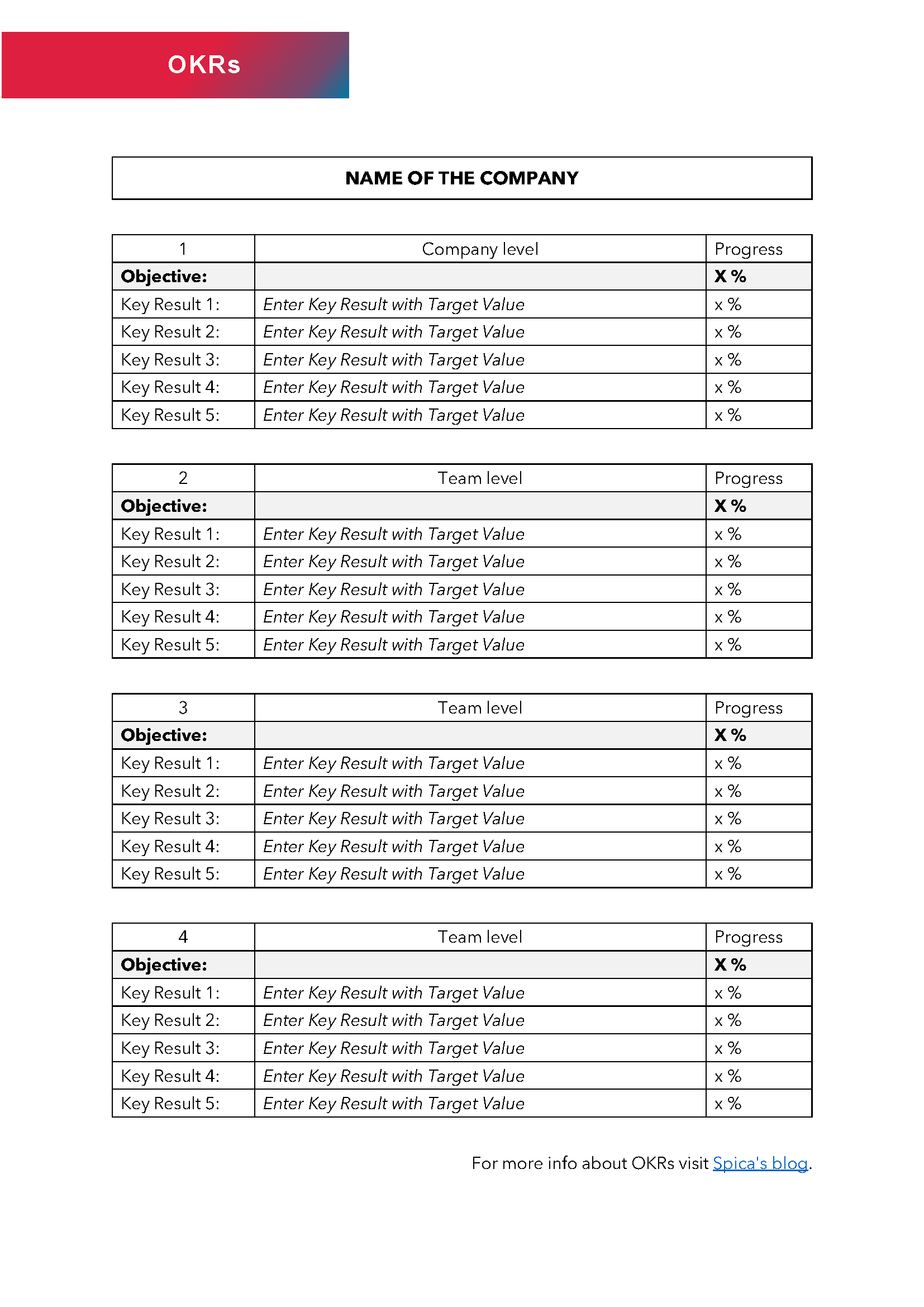

The OKR tools and additional resources available

Since the OKR technique is very popular, there are many different tools available. In general, you can use:

- A software solution

- A template – document or spreadsheet

There are more than 50 dedicated OKR solutions or project management tools with implemented OKR features. The most popular solutions are: Weekdone, Gtmhub, Perdoo, Profit.co, Plai, and Simple OKR.

If you are new to OKRs, it might not be best to immediately go with a software solution. The first step should be to master the technique, and you can use a template for that. Then, after mastering the technique and scaling it across the company, OKR software can be of great help.

That brings us to an OKR template. We have provided you with one that you can download below. You can adjust the templates to your needs however you wish.

And if you would like to learn more about the OKRs, please check out these useful resources:

- Measure What Matters by John Doerr

- TED talk by John Doerr

- Radical Focus by Christina Wodtke

A brief history of OKRs

Last but not least, let’s look at a brief history of OKRs. The basis for the OKR methodology was designed by Andy Groove, who used to be CEO of Intel.

He wrote a book called High Output Management, in which he described the iMBOs technique used in Intel, which stands for Intel Management by Objectives. The iMBO was the starting foundation for OKRs.

Then the technique was upgraded to OKRs and popularized by a venture capitalist John Doerr, who worked directly with Andy.

He has a famous TED talk on the subject and also wrote a book titled Measure What Matters (you can find a link above). He was an investor in Google and introduced the OKR technique to Google’s founders. They adopted and popularized it even further.

Today OKRs are used by many corporations, especially tech giants such as Google, Intel, Microsoft, LinkedIn, Twitter, Uber, Netflix, Spotify, Airbnb, IBM, Dropbox, and many known non-tech companies such as Disney, BMW, Deloitte, and the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation.